A Verified Train Protection System

This post is targeted at a non-formal methods audience and provides the motivation and overview for our work on verified train protection systems.

Train protection systems safeguard railroad operation by keeping motion within a safe envelope, deciding when to slow trains down to avoid collisions with other trains on the track, stay inside movement authorities (the region of the track that a signaling system allows a train to be in), and navigate slopes, curves, and tunnels safely. Given the frequency and severity of train safety incidents around the world, train protection software has a vast potential for positive impact. But how do we make sure that the train protection software itself is correct? The current standard in industry is to run extensive, expensive tests and simulations. While this testing goes a long way in catching bugs, it is not infallible. One can hardly test for every possible train velocity, every possible terrain, and every possible train consist because there are infinitely many possibilities. Reality restricts engineers to performing a finite number of tests, checking only a small fraction of the infinitely many situations that a train protection system might face. Train motion is complicated and involves many parameters, as is train infrastructure, with many moving parts and communicating subsystems. Testing is simply too limited a technology to check every scenario and catch every bug.

Formal Verification

This is where formal verification enters the picture. The idea is to model the train control software, train subsystems, and dynamics mathematically, in a suitable logic. Within this logic, following mathematical rules, we write a proof of safety, an argument consisting of a series of mathematical steps that establish that the logical expression for “this train protection system ensures that the train never exceeds its movement authority” follows from stated assumptions about how trains behave and the operational settings under which the controller is running. The nice thing about mathematical proofs is that when they succeed, they provide a complete guarantee, checking safety in every modeled scenario. Thus, a single formal proof corresponds to infinitely many simulations.

To get a really rough idea of how this idea of guaranteed correctness might work, think back to middle school math.

Suppose you know that v^2<u^2+x and x<42 where u and v represent initial and final velocity of an object, and x, the distance traveled.

You now want to check if v^2<42.

On the one hand, you could write a simulation: run a program that assigns different values to v, u and x, and check if things work out.

But there are an infinite number of combinations of v, u and x; you will never be able to check all the possibilities.

But instead, mathematical rules allow us to perform algebraic transformations that are always correct.

Because the square of a real number is non-negative, 0<=u^2. Combining this fact with v^2<u^2+x, we can conclude v^2<0+x, which simplifies to v^2<x.

Then, combining v^2<x with x<42, we can conclude v^2<42.

By using mathematical rules, we were able to derive the conclusion we were interested in checking with 100% certainty.

Train controllers are certainly a lot more complicated, but the same idea applies: use mathematical transformations to derive conclusions about the controller with certainty.

In contrast with this example, where the conclusion, v^2<42, was immediate and unexciting, a symbolic proof would provide significant value in concluding the correctness of a train protection system: without a formal proof, it is practically impossible to be fully confident that you have checked, through simulation and testing, all the “important” scenarios for train control.

To further preclude the possibility of human error in the math, a computer checks the proof to certify that it works out.

Being certain about correctness is very valuable. Not only does it save lives and provide peace of mind, but also, precision in reasoning can permit more aggressive, efficient train operation. No longer would engineers have to leave large, conservative margins for the errors that they cannot currently reason about precisely. Trains scheduled closer together can mean increased throughput. Likewise, as trains driven by artificial intelligence become a possibility, it would be more important than ever to secure efficient but poorly understood machine learning-based decisions within trustworthy, highly reliable train protection software. Knowing that the train protection software handles every edge case correctly becomes essential. Formal methods-based verification can also make it easier to handle updated system requirements than a simulation and testing approach to validation, resulting in faster development cycles. Instead of rerunning an entire test suite, only relevant modification in the proof would be required.

A Proof of Concept Verified Train Protection System

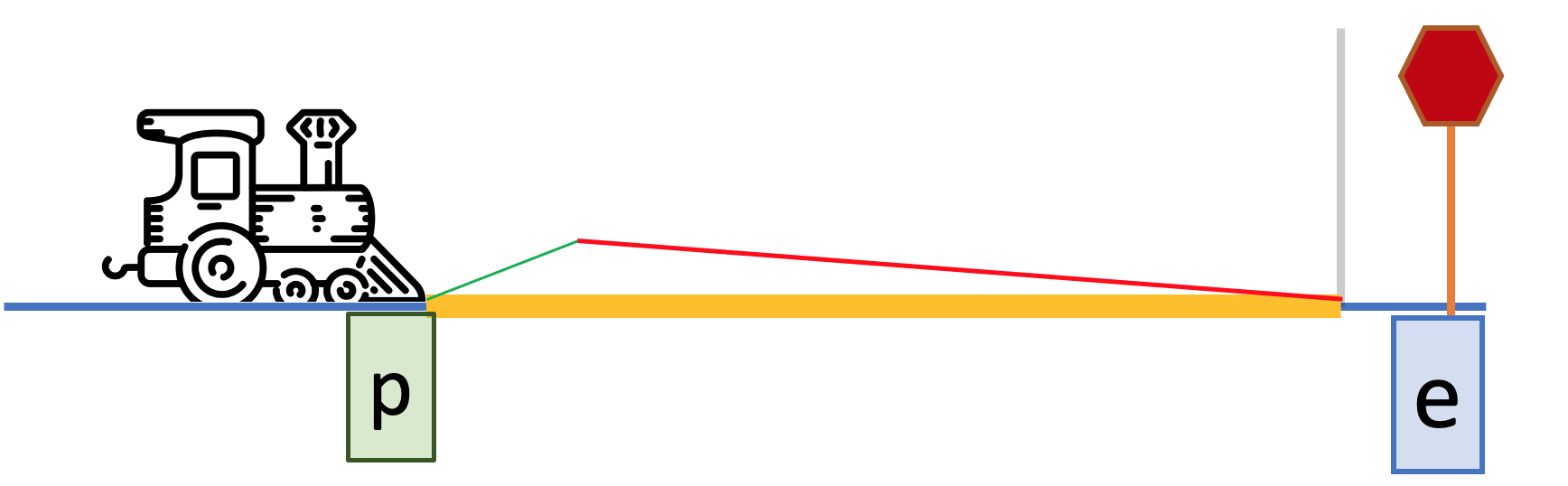

As proof of concept, we created a verified train protection system [1]. We proved the train protection safe against the train kinematics model from [2] (the FRA paper that develops a PTC braking algorithm for freight trains). We sought to design a mathematically sophisticated train protection system that was provably safe while still being as efficient as possible. The technical challenges are summarized in our paper at EMSOFT 2022, and also in this video of the corresponding talk. Our verified train protection system is written with non-determinism and thus represents multiple controllers, all proved safe at once. Each controller can be extracted by resolving the non-determinism in different ways, (for example, optimizing for energy efficiency), and inherits the safety proof automatically. Thus, the verified train protection system can be seen as an envelope around safe control. This envelope around safe control actions is not to be confused with motion authorities or moving blocks, which are envelopes around train position. The fact that our system is a non-deterministic control envelope means that existing control systems, whether human or automated, can also run inside it for an extra level of safety.

Running some experiments to understand the behavior of our system, relative to the PTC algorithm specified in [2], we found scenarios where the verified protection system achieved a 4X reduction in the undershoot (train stopping before it is required to, because of conservative reasoning about errors) during braking enforcement. Less undershoot can mean greater train throughput and therefore increased efficiency. At the same time, in all the scenarios we checked, our system successfully prevented overshoot (the train going past the end of motion authority, which is a safety violation, to be avoided at all costs). The train protection system that we created was symbolic, meaning that by substituting concrete values for the various parameters via the appropriate methods [3], we can easily obtain concrete verified train protection systems tailored to specific railroads and trains. A verified conversion pipeline [4] allows us to go from our the proof written in logic to verified code that runs on actual computers automatically. I am interested in closing the gaps between our research and what industry would find useful in practice.

References

[1] A. Kabra, S. Mitsch and A. Platzer, “Verified Train Controllers for the Federal Railroad Administration Train Kinematics Model: Balancing Competing Brake and Track Forces,” in IEEE Transactions on Computer-Aided Design of Integrated Circuits and Systems, vol. 41, no. 11, pp. 4409-4420, 2022, doi: 10.1109/TCAD.2022.3197690.

[2] J. Brosseau, B. M. Ede, S. Pate, R. Wiley, and J. Drapa, “Development of an operationally efficient PTC braking enforcement algorithm for freight trains,” Tech. Rep. DOT/FRA/ORD-13/34, 2013.

[3] A. Platzer, “A complete uniform substitution calculus for differential dynamic logic,” J. Autom. Reas., vol. 59, no. 2, pp. 219–265, 2017.

[4] R. Bohrer, Y. K. Tan, S. Mitsch, M. Myreen and A. Platzer, “VeriPhy: verified controller executables from verified cyber-physical system models”, PLDI 2018.